A new paper by Cortelyou C. Kenney explores recent developments in game theory to question some of the fundamental assumptions of classical law and economics scholarship, especially the scholarship of John Nash. She suggests that a more sophisticated understanding of cooperation can create fairer and more just institutions that maximize social welfare instead of individual efficiency.

Most modern game theory is deeply indebted to ideas of efficiency and rational actors. These principles are woven into the incentive structures that different bodies of thought that inform jurisprudence and policy, from law and economics to mainstream economics and mainstream computer science, propose to encourage good behavior and punish and deter bad behavior. The most famous proponent and the person most associated with the development of efficiency-maximizing game theory is John Nash.

Game theory is perhaps best exemplified by the thought experiment “The Prisoner’s Dilemma.” Nash’s dissertation adviser Albert Tucker invented The Prisoner’s Dilemma to predict how rational actors will behave to maximize their utility. In the traditional formulation, two co-conspirators to a crime are separately detained, isolated, and interrogated by the police. The co-conspirators are faced with two options: unilaterally cooperate with their co-conspirator and stay silent during the interrogation or defect and inculpate their co-conspirator. The co-conspirators do not know how their co-conspirator will act, and if one stays silent while the other defects, then the one who talked will go free while the one who remained silent will go to prison for a long time. In the event that both stay silent, both will receive a reduced sentence. In the event both talk, both will go to prison for a long time.

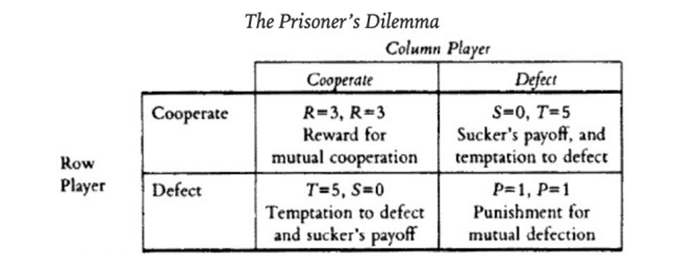

One version of the payoff matrix is displayed below and shows the four possible outcomes to the Prisoner’s Dilemma: cooperate, cooperate (CC); cooperate, defect (CD); defect, cooperate (DC); and defect, defect (DD).

The Prisoner’s Dilemma and similar games are used to justify legal intervention when rational individual behavior risks producing a sub-optimal, inefficient collective outcome. As University of Chicago legal scholar Randy Picker explains:

The power of the Prisoner’s Dilemma comes from the incongruence between private benefit and the collective good. Individually rational decisionmaking leads to collective disaster. The Prisoner’s Dilemma is thus often seen as one of the main theoretical justifications for government intrusion into private decisionmaking.

For example, many game theorists in the Chicago School use game theory to rationalize aspects of the legal system, such as laxer regulation of utilities or polluters. Some of these Chicago School game theorists, building on Nash, conclude that it is in the best interest of the government not to allow all pollution, but to allow at least some pollution because shutting down factories that pollute will put blue-collar workers out of jobs. Alternative game theory models would find this “optimal” level of pollution to be in fact sub-optimal.

Alternative Game Theories

The traditional Prisoner’s Dilemma has several built-in problems for the players which do not reflect real-world applications, including a lack of communication between the prisoners and inability to trust in the good faith of other players. Most importantly, it is predicated on the assumption that the two co-conspirators do not know each other well, and thus lack a “mental model” of the other player or any long-term sense of obligation to them because there is no possibility of another encounter. The Prisoner’s Dilemma offers a Hobbesian view of “social interactions.”

But if the game is played repeatedly—in a variation referred to as the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma (IPD), where the same two players encounter the dilemma over and over and can form a long-term relationship—strategies for cooperation begin to emerge. These long-term interactions change the theoretical outlook of the game, as well as the practical insights that can be derived from it to help promote cooperation on the ground.

In response to these problems, computational biologist William Press and physicist mathematician Freeman Dyson developed a new version of game theory that allows a player with a “theory of the mind” (i.e., a player who realizes that their behavior can influence their opponent’s subsequent strategies) to defeat players in games without one.

Press and Dyson labeled this new class of strategies Zero Determinant (ZD) strategies. Alexander Stewart and Joshua Plotkin have built on the ZD insight to show that, under the correct conditions, the winning strategy to the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma does not involve coercion and exploitation but maximizing cooperation.

ZD Game Theory and Real-World Applications

An iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma provides insights to resolve intractable social problems that the traditional versions of Nash and the Chicago School could not. One prominent example is the “tragedy of the commons,” wherein self-interested individuals will deplete a common resource to the negative welfare of all.Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied local communities from around the world to show that local communities can cooperate to protect communal resources and improve aggregate welfare, though at the end of her career she said that cooperation would require many complicated factors.

In one illustration of this deviation from traditional game theory, Andrew Tilman, Simon Levin, and James Watson studied fisheries to show that the goal of efficiency or individual resource maximization is not necessarily the best for the community in all scenarios. Better was to pursue a second best or sub-optimum individual catch level that enabled fishers not to overfish and to agree to limit their consumption in a sustainable way. The authors found that fisheries voluntarily departed from Nash levels of consumption, and instead consumed what was socially optimum.

What does an alternative view of the legal system look like based on game theory that prioritizes cooperation and even fairness instead of efficiency? To take an example, think of the property law system. Sonia Katyal and Eduardo Peñalver suggest the property law system should not be based on a system of ownership but rather should be based on a system of “stewardship,” where individuals who are in possession of property (be it land or an object) view themselves as stewards for future generations and who pass down responsibility for property to their progeny. In my own research, I argue that stewardship can be used to regulate physical and intellectual property and, similarly, that rather than owning property, individuals have an obligation to future generations.

To think more concretely, consider climate change. First, a “stewardship” view would require large companies to acknowledge that efficiency is not the only value that matters, and indeed values of fairness and maximizing social utility are more important. A stewardship model of property premised on fiduciary duties, for example, would require oil companies to use the same technologies abroad they use in the United States, which certain companies fail to do, resulting in large environmental disasters.

Second, a fiduciary model would similarly have companies hold a duty not only to their shareholders but also to future generations. This would require companies to be transparent about the impact of their activities on social welfare and to take efforts to adapt to social needs rather than bend government regulation to their strictly financial self-interest. For example, in a groundbreaking paper in Science, Harvard researchers discussed evidence that gas and oil giant ExxonMobil had known “since the late 1970s that its fossil fuel products could lead to global warming with “dramatic environmental effects before the year 2050.” In another example, the documentary Who Killed the Electric Car? explored the role oil and gas companies played in stopping early efforts from car manufacturers to develop electric cars during the 1990s and early 2000s.

A stewardship model as an alternative to the current property law system could have prevented firm behavior resulting in socially undesirable behavior, including the mitigation of climate change. The stewardship approach argues that individual businesses in tandem with the government have an individual duty to act in a green fashion and to prioritize sustainable development.

Iterative game theory based on ZD strategies is not the only evolution in game theory to move away from traditional models. Recently, the U.S. military and the RAND Institute in Santa Monica have used multiplayer game theory that goes beyond the Nash two-player games to understand how climate change, which they characterize as an emergency situation, could lead to different responses to catastrophes in developing countries. It is clear that the game theories of Nash and the Chicago School are too simple to capture the multifaceted and iterative nature of real-world scenarios.

***

Critics of Nash’s cynical game theory mode and the Chicago School’s law and economics scholarship premised on the selfish, rational actor often point to the fact that real world decisions are not made in isolation but include an iterative process where actors can communicate and form relationships that allow collective decisions that enhance aggregate social utility. The failure of neoliberalism, much of it underpinned by law and economics scholarship, to address social issues such as income inequality, racial justice, and property law show that old paradigms of utility-maximizing behavior are not working. Developments in game theory by me, Press, Dyson, Stewart, and Plotkin suggest a more sophisticated understanding of utility achieve through cooperation. Certainly, issues remain in these iterative models of game theory, including how to create enforcement mechanisms or develop incentives to prevent “cheating” and “free riding.” Ultimately, new systems may be necessary to account for enforcement problems based on the theory of win-win solutions.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.