Rodrigo Castro Cornejo discusses the reasons for the rise of left-wing populism in Mexico under Andrés Manuel López Obrador, how López Obrador’s administration has changed Mexico’s political economy in his six years in office, and what this means for the future of populism in Mexico as voters head to the polls on June 2.

This article is part of a series seeking to understand the issues of political economy driving populist movements around the world as we proceed through the “year of elections.” We will publish a new article every week, which you can find here.

For the last decade, populism in Mexico has been defined by Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his leftist MORENA party. Leftist rhetoric railing against neoliberalism has characterized López Obrador’s version of populism, although policies in practice have reflected the ideological spectrum, including austerity. This article will explore the facets of López Obrador’s populism, the economic reasons voters have supported it, and what this means for the future of populism in Mexico as the country heads to the polls on June 2.

The Rise and rhetoric of Andrés Manuel López Obrador

Before the 2018 presidential election that handed power to MORENA and López Obrador, the party system in Mexico was one of the most stable in Latin America. Since Mexico’s transition to a real democracy in 1997, the centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the center-right National Action Party (PAN), and the center-left Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) have battled as the three main parties in Mexico. However, voters soured on these parties as the PRI and PAN administrations experienced corruption scandals and mixed economic, income, and job growth.

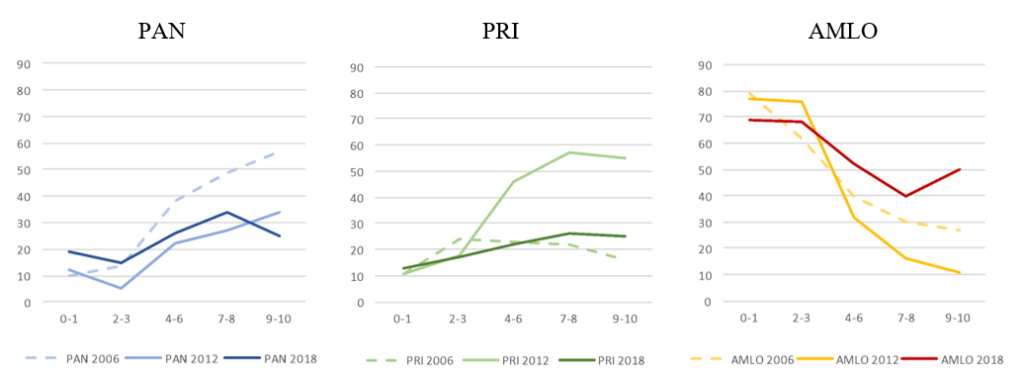

In 2018, MORENA and its presidential candidate, López Obrador, won both the country’s presidency and the legislative majority with its partisan allies in Congress. López Obrador took 54.7% of the presidential vote after receiving 32.4% in 2012 and 36.1% in 2006. López Obrador won the presidency on his third attempt by appealing to a broad multi-class coalition of voters. He received similar support from men and women, less educated and highly educated voters, younger and older generations, and rural and urban voters. What is most notable, though, is how much of his victory can be attributed to his appeal to conservative voters. In 2006 and 2012, he received 27% and 11% of the vote from those who identified as most conservative on a 0-10 left-right scale. In 2018, he received 50% of the vote from this demographic, according to the Mexican Election Study (figure 1).

Figure 1. Vote for PAN/PRI/AMLO across ideological groups (2006-2018)

López Obrador was able to appeal to such a wide range of voters by avoiding explicit policy proposals as a candidate. Instead, he took aim at the corruption of the PRI and PAN governments that had dominated office since 1997 and blamed their neoliberal policies for a lack of economic growth and widespread poverty. In fact, López Obrador’s 2018 victory may be attributed more to voter rejection of the mainstream parties, particularly the PRI and PAN, than the appeal of López Obrador’s platform outside being the choice for change.

As a candidate, and then as president, López Obrador’s rhetoric, especially against neoliberalism, has emphasized an economic agenda championing support for the poor, strengthening Mexico’s state-owned oil industry and infrastructure projects, and fighting corruption. He makes efforts to distinguish the good, common people from the corrupt elite, the “mafia del poder” (political mafia), who allegedly robbed him of the presidency in 2006 and 2012 and have impoverished Mexico through neoliberalism and corruption.

His emphasis on resonant aspects of the political economy has come at the expense of social issues, such as gender equality and abortion and LGBTQ+ rights. His government has distributed a handbook on morality called the “Cartilla Moral,” which laments the “loss of cultural, moral, and spiritual values in Mexico.” López Obrador has also warned against the legalization of drugs and his government has advanced harsh policies to stop immigration from Central America to the United States. This in part marks a reverse from his early administration, during which he took a more humanitarian approach to immigration and called Mexico a “country of refuge.” However, unlike in the U.S. or Europe, it is fairly common in Latin America for politicians to espouse leftist economic policies while dismissing or outright opposing a progressive social agenda. Hugo Chavez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Pedro Castillo in Perú, and Rafael Correa in Ecuador are all other examples of this trend.

López Obrador’s populism is also notable for the range of illiberal actions his government has taken against democratic institutions. These include appointing loyalists to the Supreme Court and forcing the resignation of a sitting justice. More recently, he tried to undermine the country’s electoral authority, the Instituto Nacional Electoral (INE), a cornerstone of Mexico’s transition to democracy, by reducing the Institute’s budget. This policy would have forced the INE to cut staff, close offices across the country, and affected the INE’s ability to organize elections. The Supreme Court eventually invalidated most of this electoral reform championed by President Lopez Obrador because of serious violations in legislative procedure-

The political economy of populism in Mexico

López Obrador’s reversal on some leftist social issues parallels the same in the economic sphere. In fact, many of his policies in office have embraced much of the Washington Consensus that he campaigned against. For example, his administration has endorsed fiscal austerity— calling it “Franciscan poverty”—and argued that by ending corruption and waste the government could continue to fund social welfare programs without raising taxes. This has led to a widening deficit, although Mexico’s overall debt levels remain sustainable. From 2017-2023, the government deficit increased from 1.1% of GDP to 2.95% (which came down from a high of 4.6% in 2020). However, the deficit is projected to reach 5% in 2024 as the government increased social spending ahead of the election. And despite augmented spending during the Covid-19 pandemic, Mexico reported the lowest level of fiscal support to mitigate its economic consequences (e.g. targeted transfers or tax cuts) compared to other countries in Latin America. In addition, a net 15 million Mexicans have lost access to public healthcare after López Obrador’s government terminated the Seguro Popular program in 2020—public health insurance for approximately 60 million people who work in informal jobs—which López Obrador identified as “neoliberal.” The Seguro Popular was replaced by different programs that did not have the same comprehensive coverage. Similarly, although poverty on the whole has decreased under López Obrador, extreme poverty has actually increased by 400,000 people due to the changes his administration made to Mexico’s social welfare programs.

On the other hand, López Obrador’s government has fulfilled some of its campaign promises, including the replacement of Mexico’s conditional cash transfer Progresa-Oportunidades program with a new one that sends direct cash transfers to marginalized social groups including students, single mothers, and young professionals. López Obrador government has also significantly increased the minimum wage, boosted labor unions, and increased public investment in infrastructure, particularly in the south, the poorest region of the country (e.g. the Mayan Train and the “Dos Bocas” oil refinery).

Indeed, López Obrador’s most notable work has perhaps been his efforts to promote the recovery of Mexico’s state-owned oil industry. During the 2018 campaign, López Obrador denounced a 2013 legislative reform by the PRI and PAN that allowed private and foreign investments in Mexico’s oil, gas, and electricity sector, and that particularly encouraged private investment in renewable energy. The goal of the reforms were to modernize Mexico’s gas industry and increase output after it had dropped precipitously for years. Upon taking office, López Obrador reimposed barriers to private and foreign investment into Mexico’s oil sector. Low global oil prices meant investment was less forthcoming than originally expected and for many Mexicans did not justify giving up sovereignty over Mexico’s resources. López Obrador has instead prioritized public investment in the fossil fuel industry, including the construction of a $20 billion oil refinery in Mexico’s poorer southern region, and dismantled the country’s publicly funded National Institute for Climate Change. As a result, Mexico is expected to fall short of its climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Like his stance on social issues, López Obrador’s economic policies resemble the economic nationalism of the populist left in Latin America that emphasize national dignity and sovereignty through the control of natural resources. As part of his energy policy, López Obrador has rehabilitated old refineries across the country and bought a new one in the U.S., stating that the refinery is now “part of the Mexican nation.” During a press conference, López Obrador noted: “we are going to be self-sufficient [stop importing gas and diesel from other countries] and we are going to make sure that oil prices are not going to increase.”

The June 2 election and future of populism in Mexico

López Obrador’s government has remained fairly popular among Mexican voters, with around 65% consistently approving of his government throughout his six years in office. However, there is some variation in approval for specific policy areas. For example, 62% believe that the president is handling social welfare programs well, but there is considerably less support for the economy (39%), the fight against corruption (38%), and security (29%). He has made little progress on the latter two items, or even seen them worsen under his leadership. López Obrador’s low marks on these latter issues, though, likely won’t matter. As I find in one study, voters will not consider these issues in isolation but relative to the prospective capabilities of MORENA’s primary rivals, the PAN and PRI, whom they still evaluate much more negatively. Recognizing this, López Obrador has continued to focus the public’s attention on the failures of past administrations rather than the victories of his own.

Constitutionally, López Obrador cannot seek reelection when the country goes to the polls on June 2. MORENA appointed Claudia Sheinbaum, the former head of government in Mexico City, as his successor. She has fully embraced “Lopezobradorismo” and campaigned in favor of continuing the “fourth transformation,” as López Obrador identifies his political movement. Mexico’s first three transformations comprise the independence in 1821, the era of reforms separating church and state in the mid-19th century, and the 1910 Revolution. Sheinbaum is running against Xochitl Gálvez, who was jointly nominated by the PAN, PRI, and PRD. According to recent polling, Sheinbaum has around 55% of vote intention while Galvez has about 33%.

This means that Mexico will likely experience another six years of populist governance. Sheinbaum has campaign in favor to continue Lopez Obrador’s economic policies and political agenda. She has endorsed controversial infrastructure projects, like the new oil refinery that the López Obrador administration is currently constructing. Like López Obrador in previous presidential campaigns, she has explicitly opposed any taxation reform and also avoided taking a clear stance on social issues like abortion. And, more importantly, Sheinbaum has endorsed the so-called “Plan C”: a series of constitutional reforms that, if approved, will undermine the Supreme Court as a democratic check to the presidency as well as weaken the independence of democratic institutions like INE, the institute that organizes national elections in Mexico. Under Sheinbaum, Mexico can expect much the same.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.