In new research, Valentino Larcinese and Alberto Parmigiani find that the 1986 Reagan tax cuts led to greater campaign spending from wealthy individuals, who benefited the most from this policy. The authors argue that a very permissive system of political finance, combined with the erosion of tax progressivity, created the conditions for the mutual reinforcement of economic and political disparities. The result was an inequality spiral hardly compatible with democratic ideals.

Is democracy compatible with large inequalities in material wealth? This question is as old as democracy itself, having drawn attention at least since the times of the ancient Greek city states. In the Politics, Aristotle put the issue quite starkly: “The real difference between democracy and oligarchy is poverty and wealth. Wherever men rule by reason of their wealth, whether they be few or many, this is an oligarchy, and where the poor rule, that is democracy.”

Contemporary democracies still struggle with the influence of money in politics. Money can be used to advocate or lobby in favor of specific policies or to gain direct access to policymakers. Wealthy individuals can acquire control of media outlets and, in this way, influence public opinion on political matters and public policy. A vast literature also consistently shows that wealthier citizens are more likely to vote and tend to be better informed on political matters: their preferences are therefore less likely to be ignored by policymakers.

Wealthy donors buy policymaking

Campaign finance is another avenue for money to influence politics. Electoral campaigns are costly, and policymakers require sizable war chests to compete. In American politics in particular, a lenient system of private campaign finance allows wealthy elites to use campaign contributions to buy political influence. Large donations might also induce legislators to overweight the political preferences of economic elites, which tend to be more conservative than the rest of the population on economic and fiscal matters.

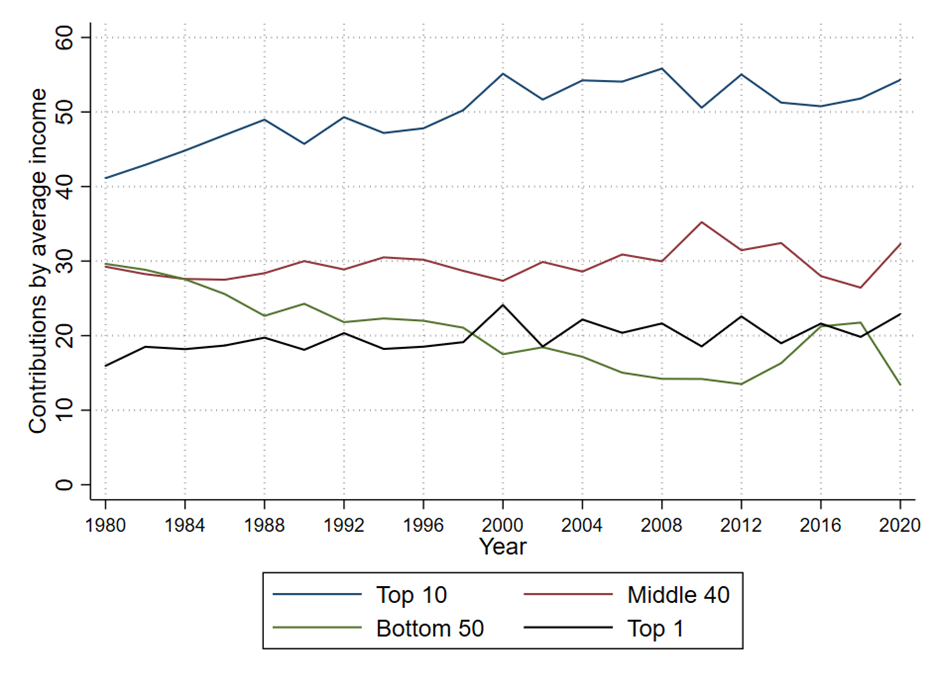

In a series of important publications, several scholars have documented the increase in income inequality which occurred during the last half-century, particularly concentrating income and wealth at the very top. In our study “Income Inequality and Campaign Contributions: Evidence from the Reagan Tax Cut,” we document a similar concentration in individual campaign contributions among the wealthy. Figure 1 shows that the share of campaign contributions coming from the top-10% wealthiest census tracts (a geographical unit slightly smaller than a zip code) went from about 40% of the total in 1980 to almost 55% in 2020. Meanwhile the share of the bottom 50% halved, from almost 30% to less than 15%. The share of the top 1% amounts to around 20% of total donations in the entire period, with a slightly increasing trend.

Figure 1: The rising concentration of individual donations

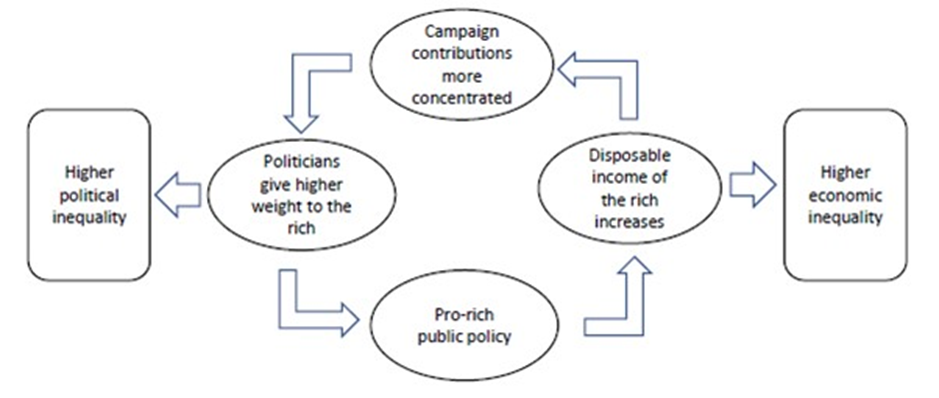

Consistent with the view that wealthier citizens exert disproportionate influence on political decisions, several survey-based studies show that public policy correlates well with the preferences of Americans in the top 10% of the income distribution. The correlation is almost non-existent for the preferences of the remaining population. If money can be translated into political power through campaign contributions and political power can be used to implement policies favorable to the affluent, this can create an inequality spiral with mutually self-reinforcing inequalities of wealth and power, as demonstrated in Figure 2. Taking taxation as an example: 1) wealthy citizens favor lower taxes; 2) tax cuts increase their disposable income; 3) having higher income, wealthy citizens spend more money in campaign contributions; 4) wealthy donors become a relatively more important source of campaign money for candidates seeking office; 5) further tax cuts become more likely, which restarts the loop.

Figure 2: The inequality spiral

But does buying political influence feed back into larger campaign donations?

There is convincing evidence that campaign contributions influence public policy. However, we are not aware of any study that addresses the other thread of the spiral: does policy-induced greater disposable income lead to larger donations from individuals in the top income brackets? This is the question we seek to answer.

To address this question, we analyze the evolution of individual campaign contributions after the 1986 Tax Reform Act (TRA) adopted by the second Reagan administration. The TRA, one of the largest tax cuts in the history of the United States, disproportionately benefited wealthy citizens and greatly increased their disposable income. Using a difference-in-differences approach and a novel dataset at the census tract level, we find that the tax savings delivered by the TRA caused an increase in campaign contributions from wealthy individuals. This rise was largely driven by wealthy census tracts and, within tracts, by taxpayers in the top 10% of the income distribution, who benefited the most from the tax cuts.

Both Democratic and Republican candidates received more donations, with magnitudes of comparable size. The post-TRA surge in donations did not correlate with the ideology of the recipients: using well-established indicators to measure the ideological leaning of members of Congress, we cannot detect any relevant differences. We find, however, that candidates who are more likely to be socially well-connected or to come from a privileged background benefit disproportionately more than other candidates.

Though it’s not all about influence

We also investigate the reasons why donors contribute to political campaigns to understand better the mechanism of this spiral. There are two main hypotheses in this regard. The first views contributions as a political investment. Donations are a strategy for individuals to support preferred candidates and policies. For example wealthy donors might contribute to candidates who will enact tax cuts for the wealthy.

The second regards donations as a form of ideological consumption. In this perspective, donations are a form of political participation that donors engage in to express their ideological preferences, without necessarily expecting any impact on subsequent policy. A branch of this view, called the “solidary motive,” presumes that donors contribute to political campaigns as part of an expected social behavior among a specific social milieu to which like-minded and influential people belong. For example, it is well known that many individuals donate when asked by friends or acquaintances.

Several studies find that, irrespective of what motivates donors, higher income tends to be associated with larger donations. We similarly do not detect any particular strategic motive behind the increase in donations after the Reagan tax cut. In this sense, our results do not support the idea of individual contributions as strategic investments. In fact, the disproportionate benefit for recipients who are more likely to be socially well-connected or from a privileged background supports the interpretation of donations as driven by a solidary motive. Large donors and recipients are parts of the same social networks and are likely to share a preference for low taxes and other policies which increase inequality. Hence, the inequality spiral depicted in Figure 2 appears to be more rooted in social class than in partisanship or ideology, since exchange and reciprocation seem to be mostly grounded on the common social background of donors and recipients.

Our conclusion, therefore, is that the inequality spiral can manifest its effects even if donors are not acting instrumentally to secure the passage of specific public policies. The combination of regressive policies with a lenient system of political finance naturally creates the conditions for the mutual reinforcement of economic and political disparities, regardless of the motivations of large donors. This combination lays the groundwork for a potential slide towards an oligarchic society, as it is shaped by social class and policies that safeguard the interests of economic elites.