Economists have become increasingly interested in questions about populism over the last decade and particularly since Brexit and the election of American President Donald Trump. However, the definition of populism remains contested. Alan de Bromhead and Kevin O’Rourke argue that economists need a better understanding of populism’s history and its variegated goals when ascribing specific characteristics and behaviors to populists and their movements.

The academic literature on populism has exploded since 2016, not just in political science but also in economics. Scholars have explored the economic and cultural roots of populism, including the role of the internet and social media, as well as its economic consequences. What can economic history contribute to the debate? In a recent paper, we argue that history should make us more careful about how we use the word “populism” and more cautious about generalizations regarding its economic and social correlates. We make three arguments. First, the late 19th-century Populist Party in the United States was not actually populist. Second, there is no necessary relationship between populism and anti-globalization sentiment. Third, the economic consensus has sometimes been on the wrong side of important policy debates involving opponents rightly or wrongly described as populist.

What is populism?

Any assessment of populism must begin with a definition, something that remains contested. Recent political science literature defines populism in a variety of ways. Perhaps the most cited definition is that of Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, according to whom populism is a “thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic camps, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’ arguing that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.” Jan-Werner Müller has a more demanding definition. He agrees that being critical of elites is a necessary condition of being a populist, but denies that it is sufficient, since so many politicians, many of whom are not apparently populist, claim that they are anti-elite and are acting on behalf of the people. In order to qualify as a populist, a politician also has to be anti-pluralist, arguing that “they, and only they, represent the people.” Populism is thus an exclusionary form of identity politics, which is why it poses a threat to democracy. The Müller definition seems the most useful and is the one we favor in our analysis—although whether “populism” is the best label to attach to it is another matter.

The Populists who weren’t

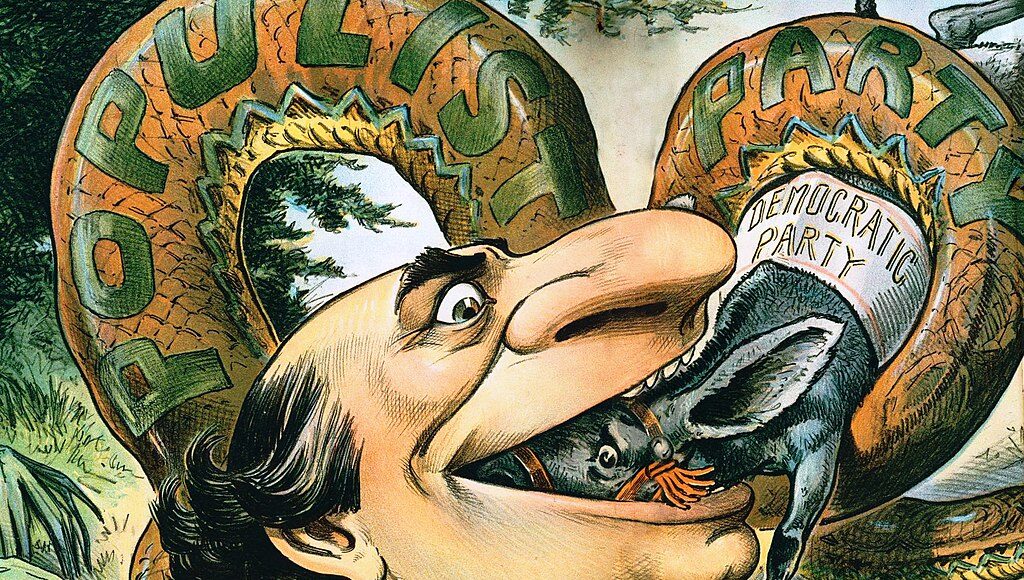

“Populism” has traditionally had negative connotations in Europe, where it tends to be understood, per Müller, as an exclusionary form of identity politics. In contrast, the word has often been used positively in the U.S. This reflects its origins in the late 19th-century American agrarian revolt, which eventually led to the formation of the People’s Party, also known as the Populist Party. While the labels we use, as well as their history, may not matter in principle, in practice they do, and there is thus a tendency for historical surveys of populism to include American Populists as an early example of the phenomenon. Whether or not the Populists were populist matters, since if they were, then populism becomes a category potentially broad enough to encompass politicians as diverse as democratic socialist U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders and former U.S. President Donald Trump.

Were the Populists actually populist? An analysis of the policies and views of their supporters suggests that they were not. As is well known, the literature on American populism has experienced notable long swings in attitudes toward the party in response to changing contemporary circumstances. The generally positive narratives of the 1930s soured in the 1950s under the influence of McCarthyism on the one hand and modernization theory on the other. The resulting image portrayed the Populists as a party of backward-looking and intolerant farmers who were largely responsible for the development of popular American anti-Semitism. If this view, famously articulated by Richard Hofstadter in 1955, is an accurate description of the Populist movement, then it would seem plausible to argue that Populists were the original populists in the sense that the term has taken on today.

Late 19th-century American Populists were certainly anti-elite. However, as Müller points out, it is difficult to argue that they claimed to represent the people as a whole, even though ”they united men and women, and whites and blacks to a degree that arguably none of the other major parties did at the time.” According to Müller, therefore, the Populists were not populist. It is true that many Populists were racist and anti-Semitic, but not all were, and so were many of their opponents. Far from being backward-looking, Populists were modern, materialistic, and dedicated to the idea of progress. They opposed monopoly power in the rail sector but were in favor of railroads. Many women were Populists. In their advocacy for a nationalized rail service, a graduated income tax, and postal savings banks, as well as their opposition to the gold standard and support of labor rights, the Populists were in many respects ahead of their time.

Populists in the 1930s

While the term “populist” may have its origins in the late 19th century, the economic, social, and political crises of the Great Depression propelled a number of populist movements to political prominence, with some ultimately being swept into power. While the German and Italian cases are well-documented, the rise of interwar populism was far more widespread.

What groups supported populists in the 1930s? While the stereotypical populist voter in a rich country today may be a blue-collar worker in a declining industrial region, we should beware of assuming that the same was true during the interwar period. Blue-collar workers did not disproportionately vote for the Nazis in Germany, for example, and when they were laid off during the Great Depression, it was towards the Communists rather than the extreme right that those with extremist inclinations turned. Instead, it was what Gary King et al. term the “working poor”—self-employed shopkeepers, artisans, professionals, small farmers, and so on—who provided the mainspring of Nazi electoral support. These differences illustrate that it is difficult to generalize about the sources of populist support across time and space.

Populism and Economics

Populists are frequently accused of, or even (by some) defined by, their advocacy of short-sighted and unsustainable economic policies. In the Latin American case, populism is often associated with irresponsible fiscal policy, inflation, and ultimately economic crisis. Recent scholarship has found a negative correlation between populist leadership and economic performance. But is populism necessarily bad economics, as Dani Rodrik has asked? What if the dominant paradigm is no longer fit-for-purpose?

American economists of the 1890s by and large viewed with skepticism the principal economic policy of the William Jennings Bryan presidential campaigns that promoted the free coinage of silver at 16-1 (16 ounces of silver to one ounce of gold) to expand the money supply in an effort to alleviate deflation. With notable exceptions, economists tended to favor the gold standard. The consensus among economists today would surely be different. Milton Friedman, with the advantage of nearly 100 years of hindsight, was sympathetic to the bimetallist cause, arguing that a bimetallic system based on a 16-1 ratio would have delivered greater price stability than the gold standard.

The gold standard is today a populist cause, advocated by sections of the American Tea Party, with the argument traceable back not to the Populists, but to their conservative opponents. Once again, if promoting harmful economic policies is a defining characteristic of populism, then it is hard to conclude that the late 19th-century Populists were populist. It was their opponents in the U.S.’ nascent economics departments who were more mistaken in their policy prescriptions. Likewise, when looking back at economic policy in the 1930s, it is widely accepted that orthodox pro-gold ideology deepened the Great Depression before Keynesian ideas eventually carried the day. Although no doubt well-meaning, policies promoted by many economists helped to create the crisis which facilitated the political ascent of populism during the interwar period.

What about another policy associated with modern populism, protectionism? Although not an explicit policy of the Populist party in 1892, the anti-tariff position of the Bryan campaign in 1896 continued the free-trade tradition of the Democratic party. Populists argued that tariffs were regressive and should be replaced with an income tax. In sharp contrast, Bryan’s Republican opponent, William McKinley, campaigned on a protectionist platform. Indeed, in the late 19th century the choice between free trade and protectionism was not a simple issue that pitted the “ordinary people” versus the “elite.” Rather, the political divisions it gave rise to were well explained by economic interests, and in particular by differing factor proportions across countries in a rapidly globalizing world. Relatively scarce factors, such as European landowners or New World labor, tended to be protectionist, while relatively abundant factors, such as European workers and New World landowners, tended to be in favor of free trade. Protectionism and populism—insofar as the latter existed at the time—were logically distinct categories, with no clear correlation between the two. Viewed in this light, the fact that 21st-century populists are often protectionist appears more to be an accident of contemporary economic history—caused by relative factor endowments of skilled and unskilled labor across the globe—than anything else, much as the logic of the Stolper-Samuelson model would suggest.

Robert Solow once argued that a key function of economic history is to remind economists that the validity of their models may depend on social context, varying across time and space. We argue that history should also encourage economists to avoid an overly simplistic view of populism and its correlates. It may seem tempting to project our present-day circumstances back onto the past, seeking to identify a package of attributes which has been constant over time: anti-elitist and demagogic political discourse, appealing to lower educated and blue-collar workers, promoting damaging economic policies, and opposing globalization in all its forms. But history is more complicated than that. Sometimes it was the elites whose policy prescriptions were both simplistic and destructive. We should not automatically assume that the economics profession is no longer capable of such errors. Few would deny that populism is a danger to liberal democracy, but as Müller points out, so too is an insistence that there is no alternative to the preferred economic policy mix of the day.

As Peter Mair has eloquently argued, democracy is hollowed out when voters are told that they can change the managers but not the policies being managed. It is precisely in such circumstances that they may turn to populism, as happened with tragic consequences in the interwar period. In contrast, when popular demands for major policy reform are satisfactorily met by democratic politicians, democracy is strengthened and demagoguery weakened.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.