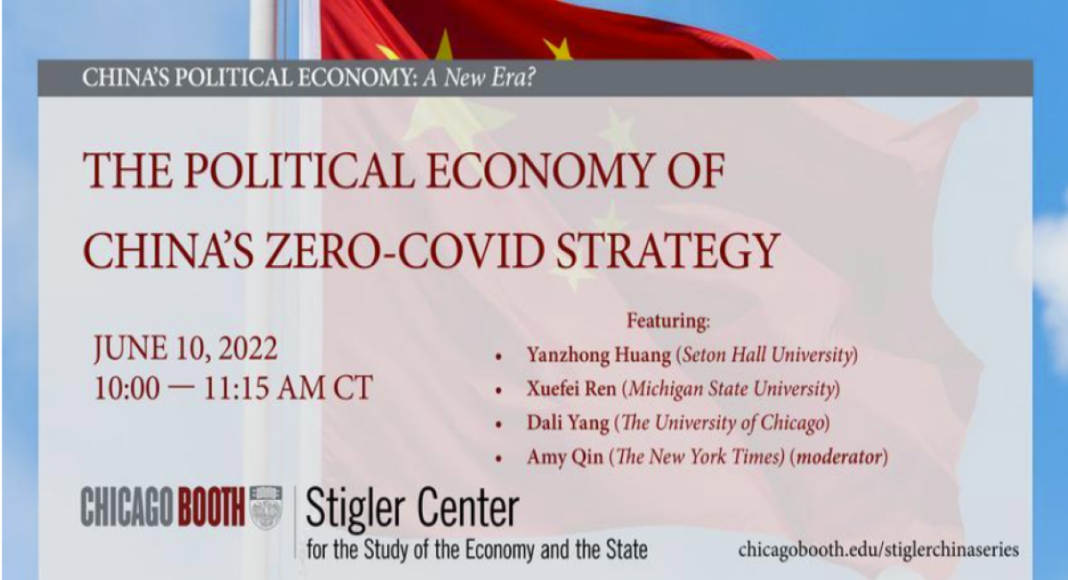

Countries around the world have overseen wide-ranging public health responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. On June 10, the Stigler Center hosted a panel of experts to discuss China’s zero-Covid response to the pandemic and how it might reconsider its policy going forward.

The Stigler Center, ProMarket’s home institute, has organized a series of webinars this year discussing different aspects of China’s changing political economy, including consolidation of political power, increasing regulatory activity in various sectors, and a renewed government emphasis on “common prosperity.” The first two webinars investigated China’s current developmental trajectory and its approach to Big Tech regulation. The third, held on June 10, delved into the country’s controversial “zero-Covid” policy, the policy’s successes, and how the policy’s reception and execution continue to evolve in response to a changing national, political, and economic context.

New York Times reporter Amy Qin, who lived in Beijing for eight years and has reported extensively on the country’s evolving Covid response, moderated the panel of three China experts: Yanzhong Huang, the director of global health studies at Seton Hall University, Xuefei Ren, a professor of sociology at Michigan State University, and Dali Yang, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago. Qin began the discussion with a reflection on how China went from losing to regaining to again losing control of the virus over the last two-and-a-half years, all while keeping its economy mostly stable. As variants changed from Delta to Omicron in 2022, however, China’s zero-Covid policy was tested significantly, from succeeding during the Beijing Olympics to failing during the Shanghai lockdown. The question now is whether this zero-Covid policy is here to stay – and how China will move on from the pandemic.

Huang explained that China first instituted its zero-Covid policy of extreme measures, including lockdowns, in response to a small number of Covid cases in the spring of 2020. As Ren noted, many cities around the world imposed lockdowns in response to Covid, and there was nothing inherently “Chinese” about the country’s approach, except its implementation, which reflected how the government managed its cities before the pandemic. Ren said this implementation relied on four essential components: low-tech barriers such as roadblocks and locking gates to residential neighborhoods; high-tech surveillance, including installing health apps on phones; social or neighborhood surveillance through street offices, police, medics, homeowner associations, and resident volunteers; and public cooperation.

The Chinese government originally designed its zero-Covid policy to buy the country time to implement mass vaccinations, Huang said. The policy successfully limited the spread of the Delta variant in the latter half of 2021 as China rolled out vaccinations, and the economy did not suffer much as a consequence. However, Huang continued to explain, the relatively low risks associated with the dominance of the Omicron variant in 2022 reignited questions about China’s aggressive zero-Covid policy and began sowing public discontent. At this point, another flaw in the Chinese government’s zero-COVID policy became apparent: The Chinese government had failed to make any long-term investment in its public health infrastructure over the last two-and-a-half years. The consequences became visible in the low efficacy rate of China’s home-grown vaccines compared to Western versions and the relatively low vaccination rate among the Chinese elderly. The zero-Covid policy became both self-fulfilling and self-defeating, Huang said. Any relaxation of the policy would lead to an uptick in hospitalizations and death.

Nevertheless, the Chinese government may now have to reconsider its policy as economic growth falters and frequent Covid testing irritates its citizens, Yang said. He noted that Chinese Finance Minister Liu Kun is trying to jumpstart the economy just as President Xi Jinping is set to take on an unprecedented third term. Additionally, the Chinese government’s thorough response to the pandemic, particularly its “double insurance policy” of vaccination and zero-Covid, has produced a paradox: the more people the country vaccinates, the more its citizens’ Covid symptoms become undetectable, making it harder to achieve a zero-Covid scenario. Yet, Yang said, zero-Covid has become enmeshed in the Chinese government’s ideology and integrated with its systemic socio-economic development, such as precision-targeted control. Unraveling zero-Covid will be more difficult than signing a piece of legislation.

So, Qin asked the panelists, how does zero-Covid end? Does the current policy still benefit China in any way? What are the implications of China’s zero-Covid policy for the rest of the world? Huang thinks the Chinese government will continue its zero-Covid policy as long as the cost of ending it exceeds its benefits. The Chinese government has politicized its Covid policy and inextricably tied its success to the success of its political system, leadership, and its leaders’ legacies. Thus, the policy’s socio-economic ramifications have become secondary. Huang outlined some scenarios in which zero-Covid could end, including China recognizing the futility of its policy after confronting the emergence of an even more contagious variant and investing in more effective vaccinations, boosters, and antiviral pills. Some scenarios could also involve the Chinese government educating its people about the true risk of the virus and implementing a triage procedure wherein it gives up zero-Covid mentality and learns to live with mild cases.

Ren and Huang think China may be closer to approaching an end to its zero-Covid policy, at least unofficially. The national Chinese leadership holds local governments accountable for both Covid management and economic growth, including job creation. As it becomes apparent that these local governments must choose between one or the other, Ren and Huang said, there may be opportunities for strategic disobedience and the implicit rollback of zero-Covid.

Panelists agreed that the impact of zero-Covid will take a particular toll on China’s agriculture and commodities industries. China has not experienced a serious recession in over 30 years, but China may have to soon depend on domestic demand to prevent economic contraction as the country experiences a reduction in employment, downward pressure on costs, and lower Chinese demand for commodities. Fortunately for China, global supply chains still depend on its muscle, and so any disruptions to China’s economy will likely be limited to sectors most dependent on domestic demand.

To wrap up the webinar, Qin asked if China is setting itself up for failure in the long run with its zero-Covid policy. The policy is costly, the virus not going away entirely, and discontent is rising. Yang pointed out that it is important to know how to define failure – the Chinese people are forgiving, he said. Ren concurred, saying that failure in the eyes of the outside world could mean success internally. “It will be interesting to see what comes next, but many of the current measures and policies are likely to survive even after the acute phases of the pandemic,” she said.