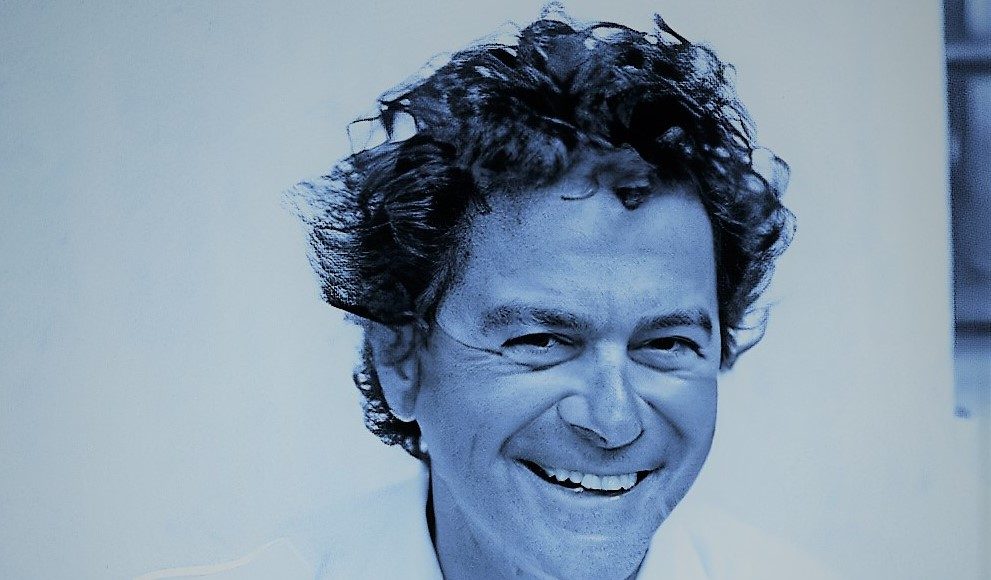

“It is a rare scholar who does research in his 60s that is as exciting as the research that he did in his 30s”: Alberto Alesina’s colleague and co-author Edward Glaeser recalls his academic and teaching achievements.

Alberto Alesina was my colleague and friend for 28 years. His scholarship was extraordinary, and his character was even better. His wit, wisdom, and warmth could light up any seminar room and even bring life to a faculty meeting. While we have lost his incandescent presence, he remains in all of us who have learned how to be better economists, better advisors, and better people, because of him.

In my memory, the sharpest moments of my decades with Alberto were the seminars in which he, or a co-author, presented their joint research. In the early 1990s, he taught us about the political forces that threatened economic growth, such as redistribution and political instability. (I was too young to be there for Alberto’s earlier work on political business cycles).

In the mid-1990s, he moved on to the political and public finance consequences of ethnic fragmentation. While that work spoke directly to America’s racial divisions, his panoramic perspective enabled him to make larger points about the political difficulties that emerge whenever populations have diverse preferences and perspectives.

That insight then led to his work on the number and size of nations. Bigger political units, such as the European Union, suffer from diversity that makes agreements difficult, as the Germans and Greeks have come to realize. That cost of size is set against the benefit of internalizing diverse externalities.

The two themes of political instability and ethnic fragmentation were merged in our joint work on why the US did not have a European-style welfare state. America’s greater ethnic heterogeneity could explain, in a simple statistical sense, one-half of the difference in redistribution levels. The other half was explained by America’s older, more pro-property, institutions. The American Constitution, unlike its European counterparts, had not been rewritten in the wake of the two world wars.

The labor supply differences between the US and Europe propelled Alesina to study the strong family ties that seem to lead to less mobility and fewer women working outside the home in Southern Europe. His intellectual course then took him back to the pre-historic plough and the origins of work specialization by gender.

A particularly striking difference between the US and Europe is that Americans believe that they lived in a mobile society, where riches are the natural reward for hard work. Europeans thought that incomes reflected luck, either at birth or afterward. These differences had little basis in reality. Upward mobility is typically higher in Europe than in the US. The effort gap between rich and poor was also higher in Europe. These facts motivated a rich series of Alberto’s papers on the formation of beliefs about fairness and redistribution, from an early multiple equilibrium model to his remarkable body of current work with Stephanie Stantcheva. It is a rare scholar who does research in his 60s that is as exciting as the research that he did in his 30s.

“He wanted students to answer big questions, and he was elated when they did.”

Every moment that we got to share on Alberto’s intellectual odyssey was exciting and illuminating. His seminars were joyous journeys into an intellectual unknown where the tools of economics were used to understand the most basic questions of politics, economics, and culture.

That same spirit permeated the seminars that Alberto attended. He wanted students to answer big questions, and he was elated when they did. He loved learning new and important things and the pleasure that came from new knowledge would shine on his face.

He felt obliged to point out obvious empirical shortcomings, which he suggested would lead to arrest or imprisonment by some nefarious group call the “identification police,” but he had little interest in sinking down to their level.

Alberto not only enjoyed making jokes, but also enjoyed jokes made at his own expense. He was frequently mocked for his limited knowledge of American arcana, such as basketball or the Midwest. Steve Levitt’s job talk (probably in 1994) concerned the impact of the Lojack anti-theft technology on auto theft in Indiana (and elsewhere).

After ten minutes, Alesina inquired as to what in the world this Lojack thing could possibly be. Andrei Shleifer immediately added that Alberto would also like to know what in the world this Indiana thing could possibly be. No one laughed harder than Alberto. He would keep laughing for the next quarter-century, where he featured uproariously in every skit show.

“There are few things more exciting than learning something new and important about humanity. Alberto Alesina never forgot that fact and never stopped bringing joy to his colleagues and students.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Alesina proved a remarkably able department chairman. Alberto may not have been the most natural bureaucrat, but his decency and good sense carried us through some of the most difficult moments at the end of Larry Summers’ Harvard Presidency. He never wasted anyone’s time and he never put any interests above those of our department.

Alberto then served many years as our Director of Graduate Studies. He displayed a remarkable combination of ambition for and empathy towards our PhD students. No one cared more about winning the annual battle with MIT to attract the best students. No one cared more about rescuing the most lost students.

I have served with Alberto on many thesis committees over the decade. My last significant email to him was a note of praise, appreciating the improvement his wisdom had worked on a particular student’s paper. I learned a great deal about how to advise from Alberto, who combined soaring intellectual hopes for his students with avuncular care for their well-being.

The quest of scholarship should be a joyful thing. There are few things more exciting than learning something new and important about humanity. Alberto Alesina never forgot that fact and never stopped bringing joy to his colleagues and students.