The negative effects of the crisis on growth will be very strong. But it will not affect everyone in the same way. If the economic decline will be most severe in the United States and Europe— as it appears now—the gap between large Asian countries and the rich world would be reduced, leading to a reduction in global inequality.

What can we say about the impact of Covid-19 on the global distribution of income?

It is hard to say anything meaningful now because we have no idea how long the pandemic will last, how many countries will be affected, how many people will die, whether the social fabric of societies will be ripped apart or not. We are totally in the dark. Most of what we say today may be proven wrong tomorrow. If someone is right, it may not necessarily be because they are smart, but because they are lucky. But in a crisis like this, luck counts for a lot.

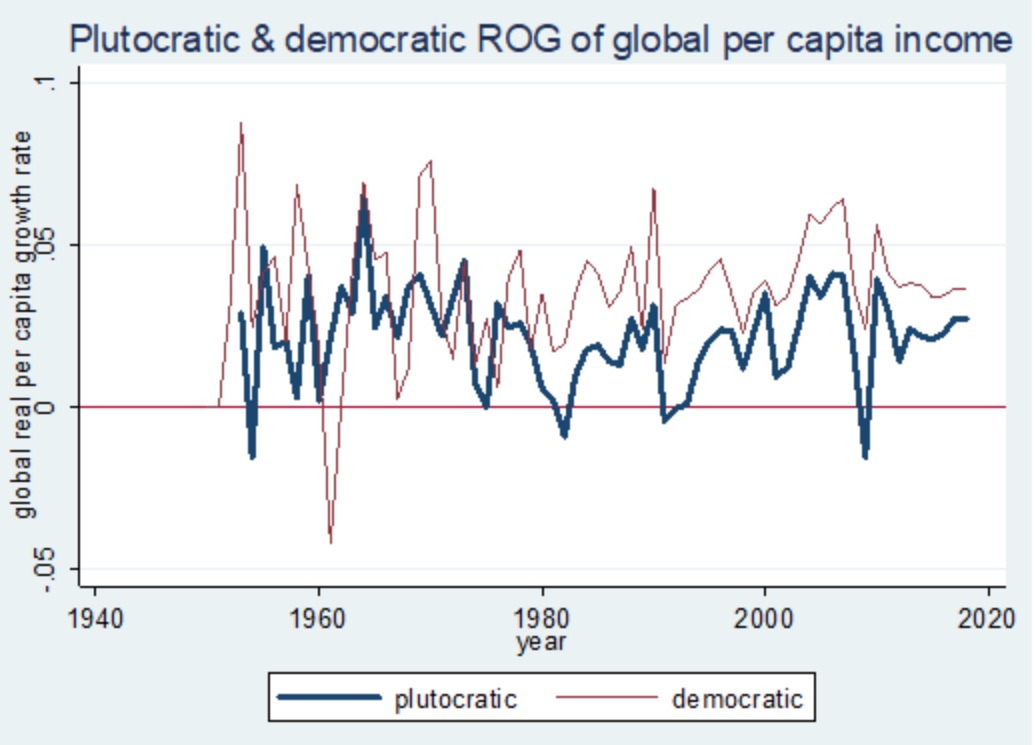

How likely is it that the crisis will reduce global income? The figure below shows global real per capita growth rates from 1952 to 2018. The thick line gives the conventional (plutocratic) measure: it shows whether the average real GDP per capita of the world had expanded or shrunk. (All calculations are in dollars of equal purchasing power.)

Global per capita GDP had gone down only four times: in 1954, 1982, 1991, and, most recently, in 2009 as the consequence of the Global Financial Crisis. Each of the four global declines was driven by a decline in the United States. This is quite understandable: The US was, until recently, the largest economy in the world; when it slowed down, it affected the global growth rate.

A different measure of global growth is the so-called “democratic” or “people’s” real growth rate (thin line in the Figure below). It asks the following question: assuming that the income distribution in each country remains the same, what was the average growth experience of the people in the world?

To put it more simply: if the GDPs per capita of India, China, and other populous countries increase fast, more people will feel better off than if some rich but small countries’ GDPs per capita went up. To put it another way: think of the time in the 1960s when the total GDP of (say) Benelux—Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg—was similar to the total GDP of China. In a plutocratic calculation, an increase of both will count the same. In a democratic calculation, an increase in China will count for much more because many more people would feel an improvement.

This second measure therefore weighs the growth rates of countries with their populations. When we use this measure, we notice that the world has never had a negative growth rate except in 1961, when the disaster of the (ironically termed) Great Leap Forward reduced China’s per capita income by 26 percent and moved the world into negative territory.

What can we say about the likely evolution of the two measures in 2020? The International Monetary Fund, which calculates only the first measure, recently estimated that the world’s GDP would be reduced by at least as much as during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The second measure is unlikely to be negative, as China is on the mend and, as we have seen, it is the populous countries that largely determine what happens to that measure.

However, we do not know how India will be affected by the crisis. If its growth rate becomes negative, it may—combined with almost-certain negative growth rates in most of Europe and North America—produce the second people’s recession since the 1950s.

| “We are thus likely to see (to some extent) a replay of the Global Financial Crisis: a deterioration in the relative income position of the West, increasing inequalities within rich countries (as low-wage and more vulnerable workers lose out), and stagnation of middle class incomes.” |

So the negative effects of the crisis on growth will be very strong. But it will not affect everybody the same. If the economic decline is the most severe in the United States and Europe— as it appears now—the gap between large Asian countries and the rich world would be reduced. This is the main force that has led to the reduction in global inequality since approximately 1990.

Thus we can expect, akin to what has happened after 2008-09, an acceleration in the decline of global inequality. Like after 2008-09, the reduction in global inequality will be achieved not through the “benign” forces of positive growth in both the rich and the emerging economies of Asia, but through the “malignant” forces of negative growth in the rich countries.

This would have the following two effects: First, from a geopolitical standpoint, the center of gravity of economic activity will continue to shift towards Asia. Whether one decides to “pivot” toward Asia or not will be increasingly irrelevant. If Asia continues to be the most dynamic part of the world economy, everybody will naturally be pushed in that direction.

Second, the decline in real incomes across Western populations follows a period in which Western economies were exiting the period of economic austerity and low growth, and one could expect that the lack of middle class growth that characterized these countries since the financial crisis would come to an end.

In pure accounting (economic) terms, we are thus likely to see (to some extent) a replay of the Global Financial Crisis: a deterioration in the relative income position of the West, increasing inequalities within rich countries (as low-wage and more vulnerable workers lose out), and stagnation of middle class incomes. The shock of the coronavirus crisis might come as the second dramatic shock to the position of rich counties within the past 15 years.

In a sense, we might expect the reversal of globalization. This is most obvious in the relatively short-term (one to two years) during which, even under the optimistic scenario of the handling of the pandemic, the movement of people and possibly goods will be much more controlled than before the crisis.

Many of the impediments to the free movement of people and goods may come from the well-founded fear of the recurrence of the pandemic, but some of them will dovetail with the economic interests of companies. Thus, the removal of restrictions will be difficult and costly. We have not removed expensive and cumbersome airplane security measures despite the absence of terrorist attacks for years, and we are unlikely to remove them in this case too.

There will also be a not-unreasonable fear that depending entirely on the kindness of strangers is not necessarily the best policy in a national emergency. This will undermine globalization as well.

Yet, we should not overestimate these impediments to trade and the movement of labor and capital. When our short-run self-interest is at stake, we are very quick to forget the lessons of history: so if several years pass without any major new turbulence, we are, I think, likely to go back to the forms of globalization that we lived through before the coronavirus crisis.

What may not go back to where it was pre-crisis, however, is the relative economic power of different countries and the political attraction of liberal (vs more authoritarian) ways to manage societies.

Sharp crises like this one tend to encourage centralization of power because this is often the only way that societies can survive. It then becomes difficult to divest of power those who have accumulated it during the crisis. Moreover, they can credibly claim that it was thanks to their ability or wisdom that the worst was avoided. Thus, politics will remain turbulent.

Branko Milanovic is the author of Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization and Capitalism, Alone, both published by Harvard University Press. He is a senior scholar at the Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. An earlier version of this post has previously appeared in Milanovic’s blog.

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.