Private donations alone cannot do much to tackle the Covid-19 health care emergency, but a more efficient allocation of this form of funding could complement and reinforce government efforts to contain and defeat the virus.

In recent weeks, crowdfunding campaigns for donations to hospitals, in Italy and elsewhere, have dramatically multiplied.

Amplified by social media postings, such campaigns make it extremely easy for everyone to contribute with a small or a large sum to cope with the Covid-19 emergency, reducing (one hopes) the risk of a collapse of health care provision in this extraordinary time. In Italy, for example, top fashion influencer Chiara Ferragni and her husband have raised more than 4m euro in less than two weeks to build a new intensive care unit at a hospital in Milan through a GoFundMe campaign.

The problem with such campaigns, meritorious though they of course are, is that there is no way for the donor to know which hospital or geographic area is most in need of their donation.

Of course, intuitively, there is more use for additional funds where the number of infections is higher, but that’s a pretty crude metric: a given area with a high number of infections may have a much better network of hospitals than another with a lower number of infections and may therefore be less in need of additional cash than the latter. Hence, one’s social media feeds risk being much more decisive in the allocation of vital private funds than if there were no information asymmetry as to where funds are most needed.

China’s solution has been unsurprisingly top-down and centralized, as Syren Johnstone has reported in the Oxford Business Law Blog: “Beijing has ordered all public donations for the Wuhan crisis to be funneled to five government-backed charity organisations,” which carries the risk of funds mishandling, as Johnstone also reminds us based on past experience.

Western democracies may, however, prefer tools that are more in line with commitments to individual freedom and decentralized decision-making, if not with people’s greater distrust in the government.

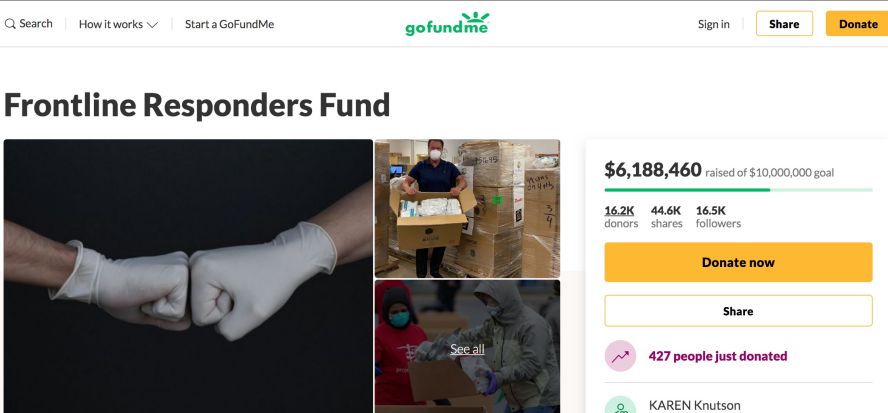

One way forward would be for governments to collaborate with donation crowdfunding portals such as GoFundMe and JustGiving. These portals are already aggregating crowdfunding campaigns to fight Covid-19 in their UK websites (see here and here). But that is not enough to compare the campaigns based on their urgency. Here, the government (whether local or national, depending on the degree of decentralization of one country’s health system) could help: it could use the data it gathers on the disease spread and its trends to create a summary indicator of the needs of individual hospitals, cities and counties, provinces or states.

For example, an algorithm could predict, area by area and hospital by hospital, the difference between the free beds in intensive care units and the foreseeable number of patients in the following ten to fifteen days, the gap between masks available and the amount needed not to endanger the health of nurses, doctors, and hospital patients, and so on: possibly, the data available to the government will not be so granular, but surely governments already have verified information to evaluate where the funding gaps are greatest: using the appropriate models, those data could be easily converted into a single funding-gap score to facilitate comparisons.

Alternatively, tech companies could easily crawl data from the internet to similarly rank crowdfunding campaigns in terms of urgency of need. Just as an example, they could use geolocation data to estimate hospitals’ overcrowding. Combined with other crude data such as Google searches of specific symptoms and other information about health care in various areas, that could also provide useful information about the relative merits of crowdfunding campaigns.

When used by donation crowdfunding portals, these scores would allow potential donors to make better choices about the hospital or the area to which to donate.

In the case of a government-created score, because the data fed into algorithm would be the same the government already uses to allocate scarce public funds orders of magnitude greater than prospective donation flows, the increase in the risk of cheating on the part of potential recipients should be low. One can also assume that governments already have systems in place to verify the data.

For example, donors could choose from week to week whether to send funds to their area of residence or to the hospital closest to their parents’ home, depending on where the emergency is greater from time to time.

The advantages of this tool are obvious.

First of all, it would not replace but complement and reinforce all current mechanisms, including the campaigns of social media influencers: influencers themselves could choose their beneficiaries more effectively.

Second, individuals’ incentives to donate would be reinforced, as they would know that they are helping where help is most needed. Nor would there necessarily be the risk of an excess of resources in the direction of a given hospital, provided the score was updated daily, having regard also to the progress of existing fundraising campaigns.

Private donations alone cannot do much to tackle the Covid-19 health care emergency. But a more efficient allocation of this form of funding is in everyone’s interest, and it would also give greater satisfaction to the many who in these days are providing excellent proof of their generosity.

Editor’s note: This post is an adapted translation of an op-ed published in the Italian daily il Foglio and available (behind paywall) here. Luca Enriques is the Allen & Overy Professor of Corporate Law at the University of Oxford Faculty of Law, in association with Jesus College.

ProMarket is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.